New UMBC-led research in Frontiers in Microbiology suggests that viruses are using information from their environment to “decide” when to sit tight inside their hosts and when to multiply and burst out, killing the host cell. The work has implications for antiviral drug development.

A virus’s ability to sense its environment, including elements produced by its host, adds “another layer of complexity to the viral-host interaction,” says Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences and senior author on the new paper. Right now, viruses are exploiting that ability to their benefit. But in the future, he says, “we could exploit it to their detriment.”

Not a coincidence

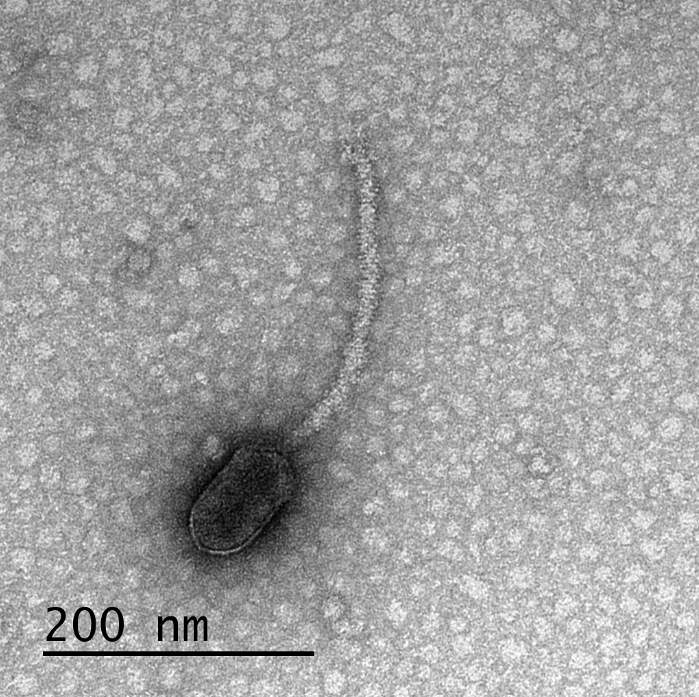

The new study focused on bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria, often referred to simply as “phages.” The phages in the study can only infect their hosts when the bacterial cells have special appendages, called pili and flagella, that help the bacteria move and mate. The bacteria produce a protein called CtrA that controls when they generate these appendages. The new paper shows that many appendage-dependent phages have patterns in their DNA where the CtrA protein can attach, called binding sites. A phage having a binding site for a protein produced by its host is unusual, Erill says.

Even more surprising, Erill and the paper’s first author Elia Mascolo, a Ph.D. student in Erill’s lab, found through detailed genomic analysis that these binding sites were not unique to a single phage, or even a single group of phages. Many different types of phages had CtrA binding sites—but they all required their hosts to have pili and/or flagella to infect them. It couldn’t be a coincidence, they decided.

The ability to monitor CtrA levels “has been invented multiple times throughout evolution by different phages that infect different bacteria,” Erill says. When distantly related species demonstrate a similar trait, it’s called convergent evolution—and it indicates that the trait is definitely useful.

Timing is everything

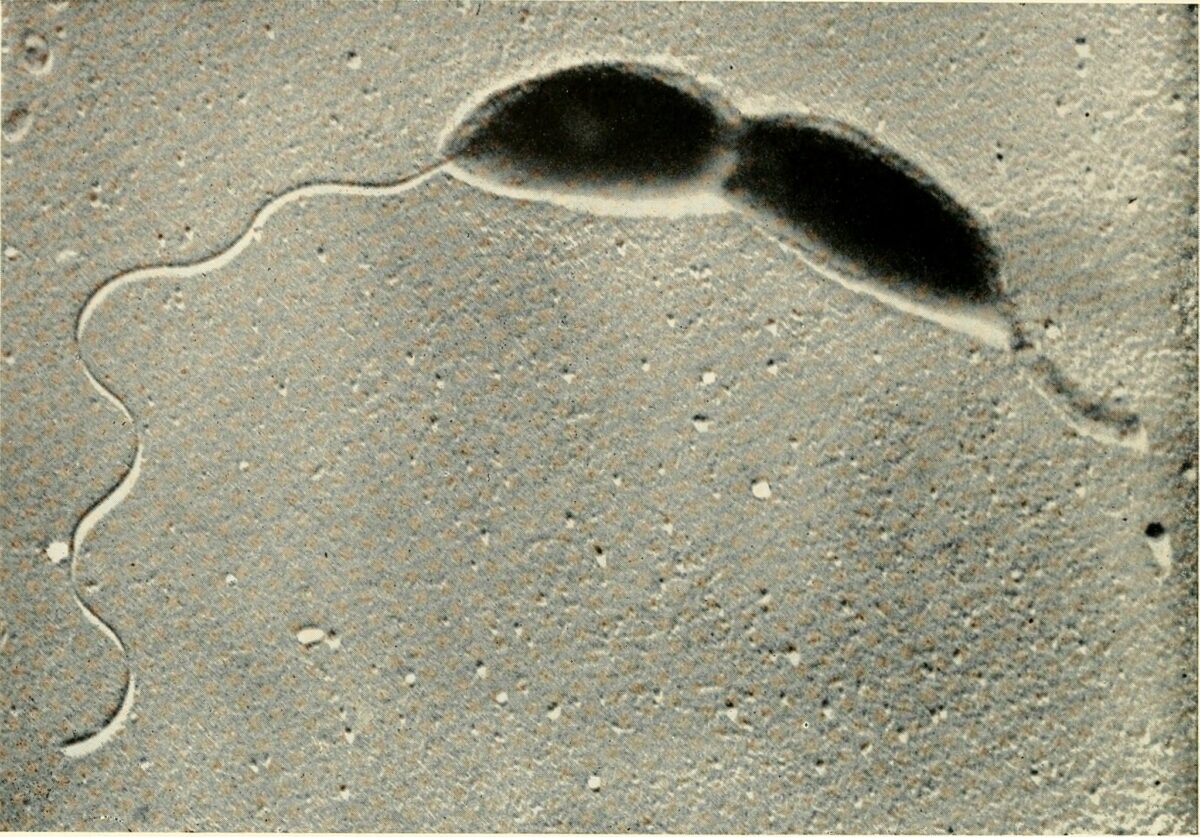

Another wrinkle in the story: The first phage in which the research team identified CtrA binding sites infects a particular group of bacteria called Caulobacterales. Caulobacterales are an especially well-studied group of bacteria, because they exist in two forms: a “swarmer” form that swims around freely, and a “stalked” form that attaches to a surface. The swarmers have pili/flagella, and the stalks do not. In these bacteria, CtrA also regulates the cell cycle, determining whether a cell will divide evenly into two more of the same cell type, or divide asymmetrically to produce one swarmer and one stalk cell.

Because the phages can only infect swarmer cells, it’s in their best interest only to burst out of their host when there are many swarmer cells available to infect. Generally, Caulobacterales live in nutrient-poor environments, and they are very spread out. “But when they find a good pocket of microhabitat, they become stalked cells and proliferate,” Erill says, eventually producing large quantities of swarmer cells.

So, “We hypothesize the phages are monitoring CtrA levels, which go up and down during the life cycle of the cells, to figure out when the swarmer cell is becoming a stalk cell and becoming a factory of swarmers,” Erill says, “and at that point, they burst the cell, because there are going to be many swarmers nearby to infect.”

Listening in

Unfortunately, the method to prove this hypothesis is labor-intensive and extremely difficult, so that wasn’t part of this latest paper—although Erill and colleagues hope to tackle that question in the future. However, the research team sees no other plausible explanation for the proliferation of CtrA binding sites on so many different phages, all of which require pili/flagella to infect their hosts. Even more interesting, they note, are the implications for viruses that infect other organisms—even humans.

“Everything that we know about phages, every single evolutionary strategy they have developed, has been shown to translate to viruses that infect plants and animals,” he says. “It’s almost a given. So if phages are listening in on their hosts, the viruses that affect humans are bound to be doing the same.”

There are a few other documented examples of phages monitoring their environment in interesting ways, but none include so many different phages employing the same strategy against so many bacterial hosts.

This new research is the “first broad scope demonstration that phages are listening in on what’s going on in the cell, in this case, in terms of cell development,” Erill says. But more examples are on the way, he predicts. Already, members of his lab have started looking for receptors for other bacterial regulatory molecules in phages, he says—and they’re finding them.

New therapeutic avenues

The key takeaway from this research is that “the virus is using cellular intel to make decisions,” Erill says, “and if it’s happening in bacteria, it’s almost certainly happening in plants and animals, because if it’s an evolutionary strategy that makes sense, evolution will discover it and exploit it.”

For example, to optimize its strategy for survival and replication, an animal virus might want to know what kind of tissue it is in, or how robust the host’s immune response is to its infection. While it might be unsettling to think about all the information viruses could gather and possibly use to make us sicker, these discoveries also open up avenues for new therapies.

“If you are developing an antiviral drug, and you know the virus is listening in on a particular signal, then maybe you can fool the virus,” Erill says. That’s several steps away, however. For now, “We are just starting to realize how actively viruses have eyes on us—how they are monitoring what’s going on around them and making decisions based on that,” Erill says. “It’s fascinating.”