A new study published in Genes may eventually give doctors the ability to make better-informed decisions about which medications to prescribe for older adults. The research, led by Mariann Gabrawy, Ph.D. ’18, biological sciences, in the lab of UMBC Prof. Jeff Leips, found associations between particular genes and individuals’ responses to a common blood pressure medication, Lisinopril. The drug also sometimes improves mobility and physical performance in older adults—but sometimes it makes things worse.

Better understanding the relationship between genetics and drug responses would help doctors prescribe drugs they know are likely to help, rather than relying on trial and error. Moving forward, researchers could employ the same experimental process Gabrawy used for other drugs.

“Our genetics matters,” says Gabrawy, who completed the research at UMBC as part of her Ph.D. dissertation as a Meyerhoff Graduate Fellow, with a UMBC-Johns Hopkins research team. “Humans don’t all react the same to various prescription medications. So it’s really important to be able to look at an individual patient and figure out if some particular medication is going to work for them or not.”

Super flies

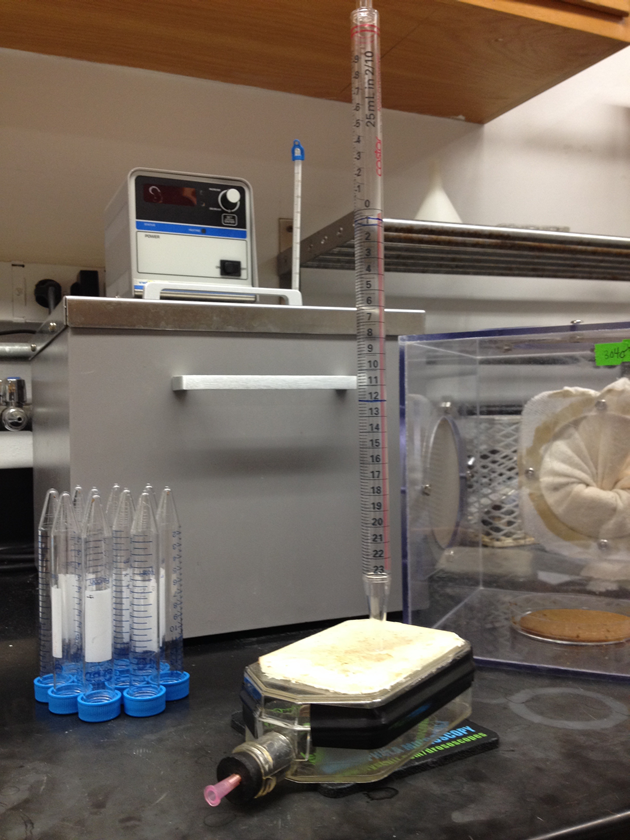

Gabrawy’s study tested the effects of Lisinopril on more than 10,000 individuals’ ability to walk and climb. What made a study of such massive scale possible? The individuals were fruit flies. Gabrawy and a team of UMBC undergraduates used a unique experimental technique to test each individual fly’s walking and climbing ability multiple times. Gabrawy developed the technique and debuted it in a previous paper.

Why is it useful to study drug responses in fruit flies? Humans and fruit flies share about 75 percent of the genes involved in disease, Gabrawy says. And the genes that she and colleagues identified as relevant to the drug response all have parallel genes in humans.

Flies also have a short lifespan, they’re inexpensive, and they’re easy to take care of, making them ideal for laboratory work. Plus, as a workhorse model species, there are hundreds of well-defined genetic lines of fruit flies that are easy to acquire, and genetic tools are readily available to apply to the fly genome.

However, of course, “You can’t just jump from a fly study to a human study,” Gabrawy says. The likely next step for studying the relationships between Lisinopril and different genes would be a mouse study, to eventually be followed by human studies. But by looking at so many flies, and identifying important gene candidates, this study “lays down a necessary foundation,” Gabrawy says.

Breaking down silos

The project also deepened ties between UMBC and Johns Hopkins University. Gabrawy was co-advised by Leips at UMBC and Peter Abadir, associate professor of geriatric medicine at Hopkins, during her Ph.D. Both are authors on the new paper.

“Research now is never one person or one research group working in a silo,” Abadir says. “I love how this research allowed us to break down the silos between UMBC and Hopkins and see the great things that each of us is doing on our campuses and what we can learn from each other.”

For example, “Mariann was able to take measures that we carry out in humans and create an analogous measure in fruit flies,” Abadir says. “That’s the beauty of working together.”

A close-knit team

Abadir was also impressed by the strength of the undergraduate researchers at UMBC, several of whom are authors on the new paper.

Leips has supported undergraduates in his research group for decades. “Kudos to them for not just doing the day-to-day work, but also contributing intellectually to the research,” Leips says of the undergraduate authors. “That’s one of the strengths of UMBC and the student population here—they really engage with the research and become real researchers.”

Gabrawy trained all 17 undergraduates who supported the work herself. Because of their efforts, collecting data took only one year, when it otherwise would have taken at least three. She still keeps in touch with her students; a few even followed her to Johns Hopkins as volunteer research assistants when she completed a postdoctoral fellowship there. Today, most of the 17 are pursuing medical or graduate school.

“It’s a beautiful thing to see that they have also found their own successes within and beyond UMBC,” Gabrawy says, “and to know that I’ve been a part of that in some small way. Mentoring has always been very important to me.”

Gabrawy has taken that spirit to her current role as a lecturer at St. Paul College in Minnesota. She is currently applying for funding to grow the college’s undergraduate research program.

Limitless possibilities

Gabrawy is focused on teaching for now, but there are plenty of opportunities to extend the work in her new paper. “One avenue of future work is to look at the mechanism,” Leips says. “We have this tie between genes and traits, but how exactly does that work at the molecular level?”

Whether or not Gabrawy and Leips pursue that question themselves, they’ve set the stage for others to do so. “The coolest part is the ability to share our findings and our data,” Gabrawy says. “We’ve provided really very important fundamental information to other scientists out there. The possibilities for future work are truly limitless.”

Header image: A student in Jeff Leips’s laboratory observes fruit flies under a microscope. Photo by Marlayna Demond ’11 for UMBC.

Tags: Alumni, Biology, CNMS, GradResearch, Research