Undergraduate research at UMBC is booming. As Undergraduate Research and Creative Achievement Day (URCAD) approaches, students across campus are preparing talks and posters on their projects with the support of faculty and graduate student mentors. Some have presented before at national and international conferences. For others, URCAD (on April 24, 2019) will be their debut on the scientific stage.

So, what creates a culture where undergraduate research thrives? Here, students and mentors across different UMBC labs share four factors they think shape the student research experience.

#1 Encourage independence to build identity as a researcher

In collaboration with their mentors, UMBC students design and implement creative and challenging research projects that directly contribute to the research mission of the lab. That independence, and the trust their mentors and labmates place in their work, contributes to the students’ development of an identity as scientific researchers.

Building confidence

Caroline Larkin ’18, M26, bioinformatics, has been working with Daniel Lobo, assistant professor of biological sciences, since April 2016. When they first met, they discussed their research interests and created a project for her that merged them together. Since then, she’s been using machine learning to define how different kinds of cells in cancerous tumors interact, because some of those interactions can lead to tumor collapse.

At first, Larkin found herself darting across the hall to ask Lobo questions frequently, but he eventually advised her to sit with her challenges for a bit first. While Lobo is still available for the tough questions, “Now I believe in myself more,” Larkin says. “I know I’m capable of fixing something in my code, for example. I give it time before I ask for help.”

“It’s my philosophy to give the undergrads an independent project that they can own,” says Lobo, with the eventual goal being that they each become first authors on a scientific paper.

Larkin is a Meyerhoff and MARC Scholar, and those programs “have really shaped my identity as a scientist, and Dr. Lobo has fueled the validation of that feeling,” she says. “I’ve always been told I was going to become a scientist, but actually doing research with Dr. Lobo has really made me feel like one.”

This fall, Larkin will continue her scientific career as a Ph.D. student in the joint computational biology program at Carnegie Mellon University and Pittsburgh University.

Tackling impostor syndrome

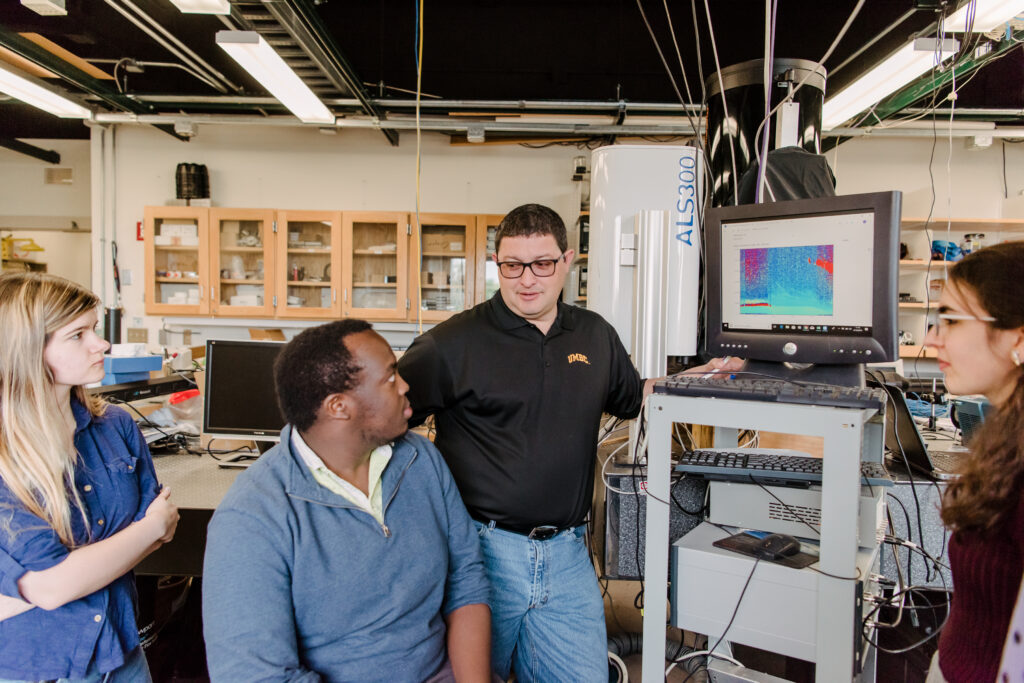

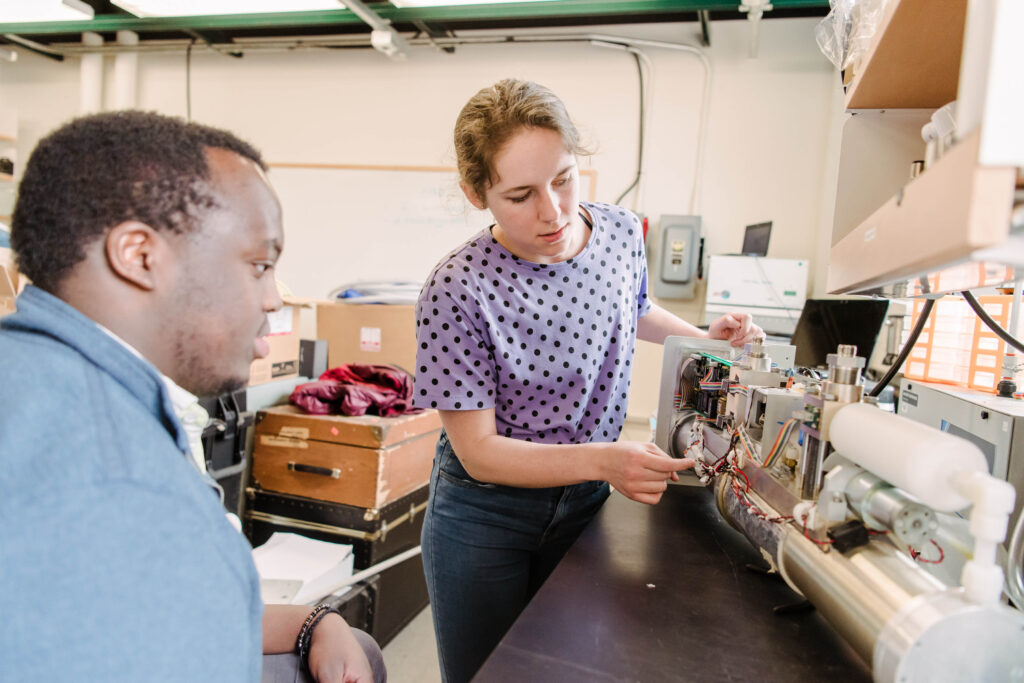

Ruben Delgado, assistant research scientist in the Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology at UMBC, instills the same kind of independence in his students. Meredith Sperling ’19, mechanical engineering and mathematics, says, “Every undergraduate has a project that they can define when they first start and then fine tune it as they move along. Graduate students and Ruben are great at providing guidance, pointing out possible pitfalls, etc., but at the end of the day it’s really our research and where we want to take it.”

Sperling’s labmate Julianna Posey ’19, mechanical engineering, says she has dealt with impostor syndrome as a female engineer, but in the Delgado lab, “both your peers and your professors take you seriously,” Posey says. “And that’s pretty uplifting.”

Jenna Westfall ’20, computer science, has enjoyed the opportunity to apply her coding skills to environmental science questions. “Looking at a problem in the real world and having to come up with my own way to tackle it has helped me professionally,” she says, “and I’m grateful to be able to work on something that benefits the lab directly.”

“This really is my project”

Kevin Chen ’19, M27, biological sciences, and Jeffrey Inen ’18, biological sciences, have become experts on their projects in Chuck Bieberich’s lab. After being mentored by Ph.D. student Apurv Rege, Chen is now the resident authority on some of the mouse lines the lab needs for its cancer research.

“When people started asking me about what’s going on with a mouse line, instead of asking the graduate student, it made me think, ‘Wow, this really is my project, and people are asking me for knowledge about it because I’m the primary source for that knowledge,” Chen shares. “I think the independence we’re given in the laboratory gives you that ownership and that feeling of being a researcher.”

This fall, Chen will take that expertise to Emory University. He’s committed to their Ph.D. program in cancer biology, where he’ll expand upon his work with Bieberich.

“He gives us a lot of independence, and I think that’s where I’ve been able to learn the most,” Inen adds. “When Dr. Bieberich starts to come to us for the answers on projects and what he needs to know for his next presentation, it makes me feel like I really belong in the lab.”

For Bieberich, investing time in his undergraduate researchers is a win-win. “As our research program has grown, it’s opened up opportunities to bring undergrads into key roles,” he says. “Having undergraduates in the lab has extended our capability to ask more complex questions than we would otherwise take on.”

#2 Support from every angle enables students to shine

Mentors who are available when you need them, understand the rigorous demands of an undergraduate science career, and can be flexible and supportive when life happens are invaluable for students deciding whether they want to start or continue in research. At UMBC, mentors proactively extend a hand to ensure their students’ success.

Investing time and care

“What I really like about Dr. Lobo is that he’s invested a lot of time into me and my project,” Larkin shares. “I know I can have an honest conversation with him when I’m struggling with something.” For Larkin, that’s included an unexpected diagnosis that left her bedridden for months. Uncertain when she would be able to return to research, Lobo was understanding and welcomed her back when she was ready.

Chen and Inen have had similar experiences with Bieberich. During a serious rough patch, “Dr. B. sat down with me and asked, ‘How can I help you?’ and we worked out a plan for him to help me through that tough time,” Chen shares. And when Inen was in the hospital for almost a week, “Dr. B. came to visit me every day,” Inen remembers. “He definitely goes above and beyond.”

On a more regular basis, “Whenever I need anything, I can just go to Dr. Bieberich and ask,” Inen says. “He’s very open to [students] coming up to him at any time, whether it’s about something in the lab or outside of the lab.” Chen agrees, sharing, “Dr. B is very supportive of everything in my personal life and in the laboratory.”

Exposure to new possibilities

Support can also come in the form of encouraging students to pursue interests beyond what they would normally consider. “The thing that I’ve always appreciated about this lab is that it’s an outlet for me to explore things outside of my engineering program,” Posey, in the Delgado lab, shares. “I’ve always been interested in meteorology and the atmosphere, and I feel like I’ve developed more of a passion for protecting the Earth.”

Delgado sees expanding students’ horizons as a major part of his role. “It’s about making them aware that they have the capacity to go beyond their own expectations and imagination,” he says. “From my own personal experience, I’m where I am because during my undergrad others provided me opportunities to conduct research. Now I’m paying it forward.”

And while he pushes them toward their potential, Westfall, Posey, and Sperling all agree that Delgado understands the demands of undergraduate life. If they need to take a short break due to a spate of exams or a family situation, there’s understanding in the lab. Between being there for emergencies and supporting students through the routine challenges of being an undergrad, UMBC mentors like Lobo, Delgado, and Bieberich create an environment where expectations are high, but flexibility exists as well.

#3 It’s all about communication

As mentors help students prepare to share their work in venues like URCAD, they also help them understand why the ability to explain research is essential for a successful career in science.

Keeping your eye on the goal

In Delgado’s lab, the message has gotten through to Julianna Posey. “The communication part of research is one of the most important parts,” she says. “You should be able to explain your research to somebody as if they’re your younger sibling. And if you can’t do that, then why are you doing it?”

With Delgado’s guidance, Posey has presented at the American Meteorological Society’s annual conference, the National Ambient Air Monitoring Conference sponsored by the EPA, and URCAD. Next year she’ll continue her atmospheric research in UMBC’s master’s program in mechanical engineering.

Meredith Sperling agrees on the benefits of communicating one’s research. “When you work on a project every day, it’s easy to get lost in the numbers,” she says. “But to be able to take a step back and succinctly present your project on a poster within ten minutes, that really keeps you on the path to achieving something that’s ultimately worthwhile, because it forces you to keep your eye on the end goal.” In particular, she says, “URCAD is important because we get to show our work to the community here at UMBC and show how we fit in.”

Getting past the fear factor

As valuable as it is, making a first presentation can be intimidating. That’s why Lobo has his students practice at weekly lab meetings. An opportunity to get feedback from trusted colleagues in a supportive setting builds confidence. So, “By the time URCAD arrives,” Lobo says, “they have presented their research ten times already, and they are not so afraid of presenting.”

It’s worked for Eric Cheung ’19, biochemistry and molecular biology, who works with Lobo. “Presenting is not really a foreign thing to me now,” he says. Plus, Lobo requires all lab members to ask at least one question following presentations. “That drove my research,” Cheung says, “to always ask one more question.”

Caroline Larkin, working in Lobo’s lab, has also benefited from gaining experience sharing her work. She and Jamshaid Shahir ‘18, mathematics and statistics, were the only two undergraduates to present at the international Winter Q-Bio conference in 2018.

#4 Diversity makes lab groups more effective

By welcoming students from all backgrounds and encouraging open communication among lab members, mentors set the stage for a research environment that is open to questions from all perspectives. That diversity in the lab benefits both students’ individual development and the research progress a lab can make.

Same questions, different tools

Lobo’s lab group includes computer scientists, biologists, and mathematicians, among other majors. That diversity benefits the work. “It’s not like the computer scientist is doing computer science, and the mathematician is doing math. Everybody is trying to answer a biological question, with different tools.”

Also, one of Lobo’s goals as a mentor is “to help students understand how science is made.” By working in an interdisciplinary team, they get a flavor for research as teamwork and the importance of approaching scientific questions from different perspectives. As a result, Lobo says, “They are going to be people who know how science works, and that can only benefit science.”

Valuing diversity

Chen and Inen both shared how much they value the diversity among the students in Bieberich’s lab, across gender, race and ethnicity, religion, language, and hometown (or country). For example, Inen is Catholic, and has valued a friendship and conversations he’s had with a female Muslim student in the lab, even attending her mosque for services. Chen identifies as atheist and feels equally comfortable in the lab.

“I look for undergraduates who are eager, bright, dedicated, and willing to put their heart and soul into a project,” Bieberich says. The makeup of the lab “just shows that those characteristics come from everywhere.”

“People from diverse backgrounds are drawn to this lab, because everyone knows Dr. B. is so friendly and kind,” says Chen. “It’s created this environment in the lab where we all learn from each other.” Inen agrees, saying, “We can talk about our differences, and it brings us all together.”

“If everyone recognizes that they’re all doing an essential part of a project that’s addressing a much larger problem, then it’s easy to step up to help each other out,” Bieberich says. “The only way we will succeed is as a team.”

For information about when these students, their labmates, and students from across all departments at UMBC are presenting at URCAD, see the full URCAD schedule.

Banner image: Undergraduate members of the Delgado research group at work. All photos by Marlayna Demond ’11 for UMBC.

Tags: Biology, CNMS, COEIT, CSEE, JCET, MathStat, MechE, Undergraduate Research