Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men other than skin cancer, with more than 288,000 new cases diagnosed every year, according to the American Cancer Society. The disease’s fatality rate has decreased by more than half since the 1990s, but there is still room for progress—especially in treating or preventing advanced, metastatic disease, which is much more likely to be fatal.

A new paper published in Science Advances, led by a team of UMBC researchers, clarifies how an enzyme called SMYD3 may be involved in prostate cancer’s progression to a more dangerous and aggressive stage. The enzyme’s newly confirmed role makes it a prime potential drug target for preventing metastatic disease.

Redefining an enzyme’s role

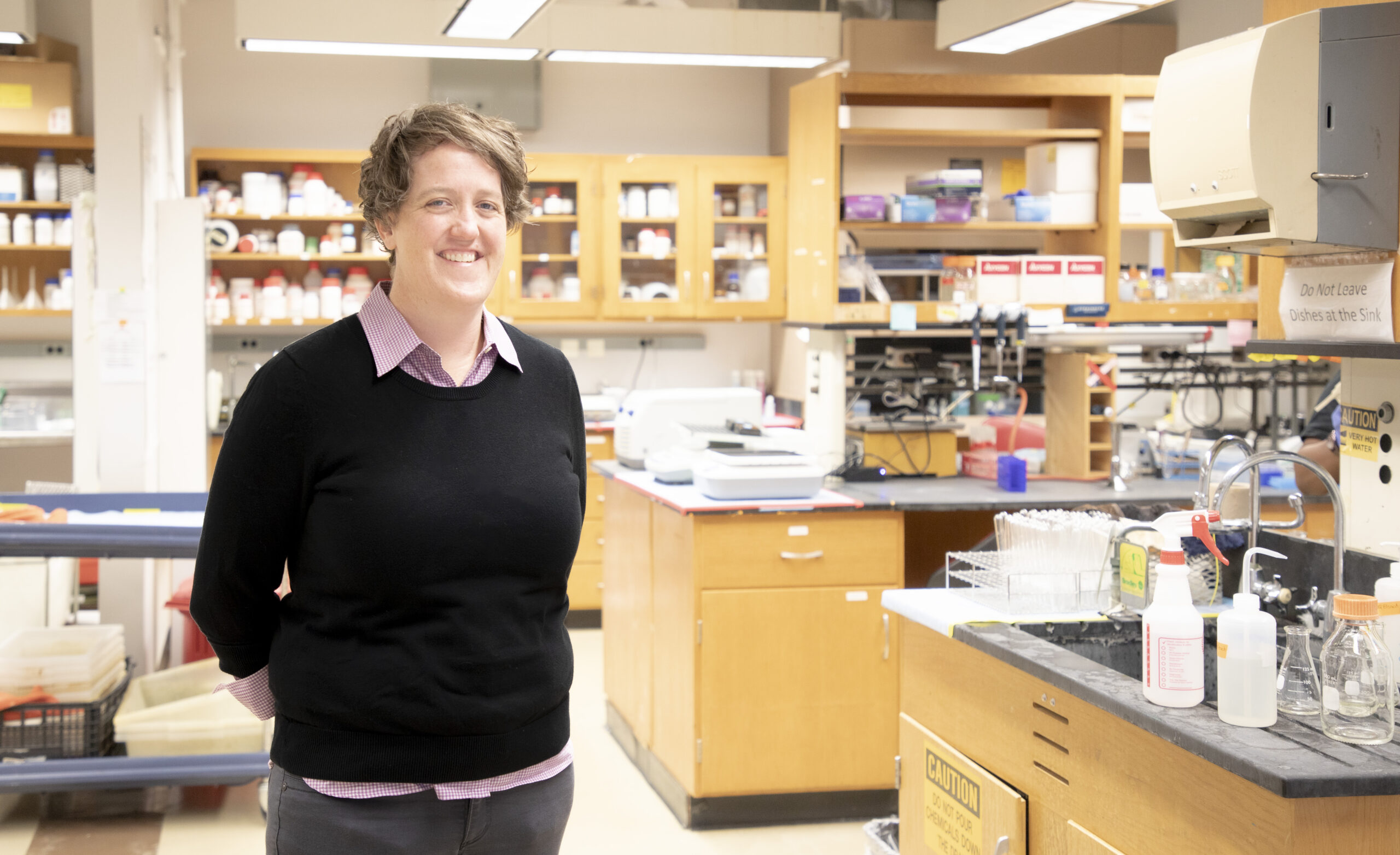

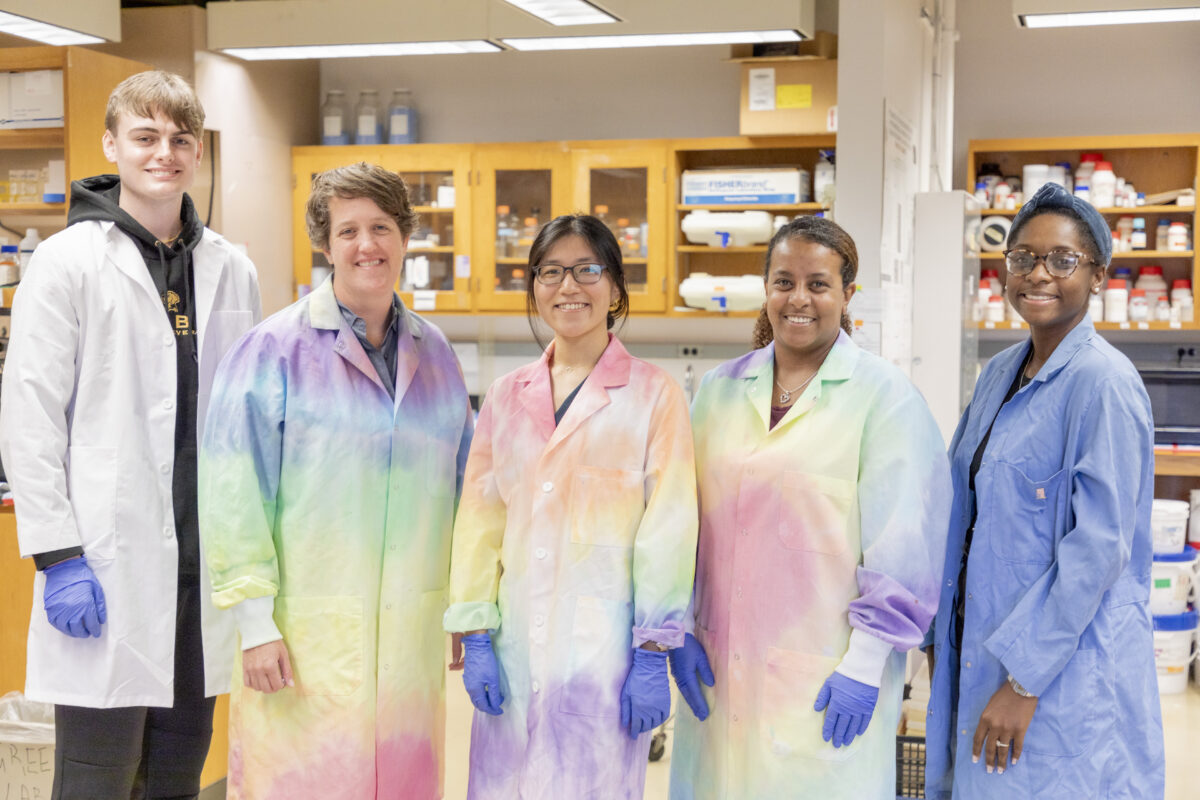

Researchers have been trying to explain SMYD3’s role in cancer since observing that it is unusually abundant in cancerous tumors, explains Erin Green, associate professor of biological sciences and senior author on the paper.

Previous studies suggested that SMYD3 acted inside a cell’s nucleus and regulated which genes the cell expressed by directly modifying DNA. But research led by Nicolas Reynoird, a scientist at the Institute for Advanced Biosciences in Grenoble, France, and a co-author on the new study, suggested a different mechanism.

In a key 2014 paper published while Reynoird was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford, he and collaborators found that SMYD3 was working outside the nucleus and activating a protein called a MAP kinase. Members of the MAP kinase protein family are overactive in cancer cells and can promote tumor growth.

The new Science Advances paper, led by Sabeen Ikram, Ph.D. ’23, biological sciences, built on Reynoird’s previous work. Ikram’s experiments showed conclusively and in more detail how SMYD3 may be triggering metastatic prostate cancer via the MAP kinase signaling pathway. The paper ties together an overabundance of SMYD3 and excessive activation of MAP kinase signaling for the first time in prostate cancer, renewing interest in SMYD3 as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer.

The new study also revealed that SMYD3 regulates a particular protein, vimentin, that is well-studied as a marker of cancer progression. Plus, the team found for the first time that SMYD3 creates a positive feedback loop in the cell, where high levels of SMYD3 contribute to maintaining its overabundance. The study’s findings relied on experiments conducted in cell lines and in mice; the latter were led by UMBC Ph.D. student Apurv Rege.

Pioneering and independent

Today, Ikram is building on her experiences at UMBC and thriving as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford in Or Gozani’s research group. Her work on the new paper was critical to its success.

“She’s extremely motivated, focused, and was really excited about the project. She just got a lot done,” Green says. “It was a new area of research for my lab, and Sabeen was willing to be independent and pioneering in getting these different types of experiments set up and figuring out what to do.”

The positive feelings are mutual. “Dr. Green’s mentorship has helped me transform from this timid, aspiring graduate student into a confident, independent scientist today,” Ikram shares. “She never stopped believing in me, especially at the times when I didn’t.”

Ikram even took unexpected challenges during her Ph.D. journey in stride. She was thrilled to travel to France for a stint with Reynoird’s research group in January 2020. Ikram planned to return in March, but had to stay until July and couldn’t enter the lab for much of that time due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Navigating 2020 was indeed difficult for all of us, but the adverse circumstances cultivated stronger friendships and working relationships” with her French colleagues, Ikram shares.

A new direction and new hope for patients

With Ikram at Stanford, and other lab members actively at work on other projects, Green is currently seeking new team members to continue this exciting line of research—and there are many avenues to explore.

“We’ve only checked this mechanism in prostate cancer so far, but I think it’s likely happening in other cancer cell types,” Green says. “That’s another thing that we want to keep investigating: How common is this?”

Green is also excited for SMYD3’s potential use as a therapeutic target for prostate or other cancers. SMYD3 inhibitors already exist, so the new findings may encourage companies to invest in discovering new uses for them.

“There’s drugs out there that haven’t been fully explored because people decided there was not a good target.” Green says. “So there’s a lot more that could be done there.”