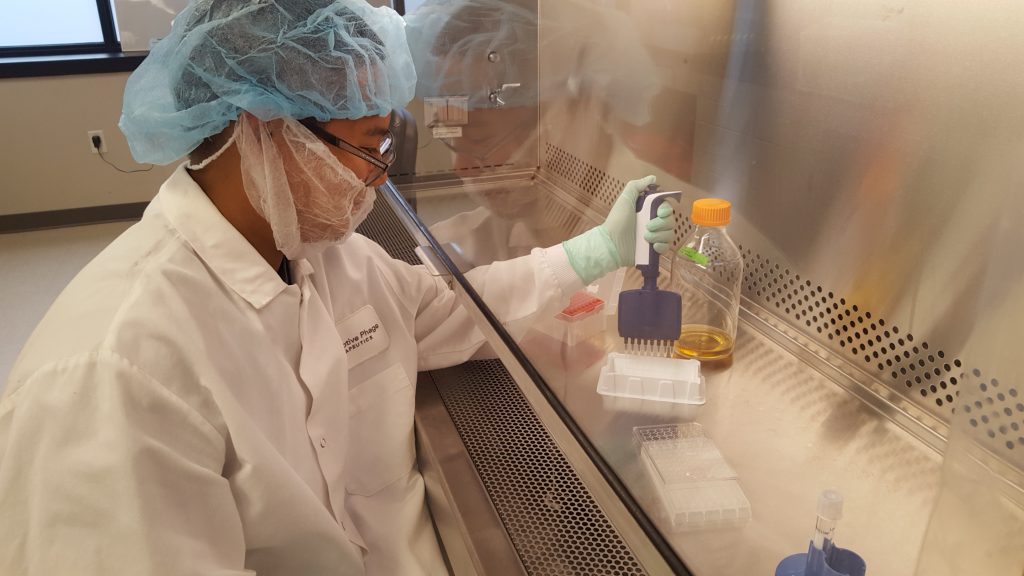

Viet Dang ’18, biological sciences, originally imagined pursuing medical school after UMBC. But when he took the Phage Hunters course to fulfill his genetics requirement, that changed. “The Phage Hunters class really opened my eyes to all the possibilities, and that I could potentially do research,” he says. Today he’s a microbiologist at Adaptive Phage Therapeutics. It’s a biotech company in Gaithersburg, MD that identifies viruses that attack bacterial cells, called phages, that can fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria for patients in need. He works alongside four other recent UMBC alumni, all of whom participated in Phage Hunters.

UMBC’s Phage Hunters program is a two-course series in genetics and bioinformatics. It aims to increase students’ awareness of their life science career options, such as the biotech industry, and give them a taste of investigative research. Launched in 2008 and based on the national SEA-PHAGES program funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, it’s making a difference in helping students see new career choices as real possibilities.

Often, if students realize medical, nursing, dental, or pharmacy school may not be for them, they leave science altogether, says Steven Caruso, senior lecturer in biological sciences and one of the Phage Hunters instructors. But the five alumni now working at APT and others “decided to stay in science,” Caruso says. “We’ve sent them into UMBC’s applied molecular biology master’s program, or into jobs in industry, and I think it’s directly because of this experience.”

Affirming experiences

Unlike Dang, Anna Kawa ’18, biological sciences, was already interested in research when she enrolled in the course. “All you had to do was sign up for the class,” she says, “and you got a spot in a lab doing wet lab work—which was exactly what I was looking for.”

The Phage Hunters experience aligns more closely with a mentored research experience than with a traditional course, as students are given significant freedom to design and complete their projects on their own schedule. The projects involve taking water and soil samples and isolating phages, viruses that infect bacterial cells. Every semester, students find phages that have never been seen before. As the organisms’ discoverers, the students also get to name the phages. At the end of the semester, the class selects a few phages to send out for DNA sequencing.

“The phages become their babies,” says Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences and the other Phage Hunters instructor. In the bioinformatics course, the students dive into analyzing the genetic sequences resulting from their discoveries in the first semester. They learn more about what genes their critters have, and at the end they submit the full genome to GenBank, a massive online database of genetic information. “I believe it’s kind of cool to be able to go to a party and say you have your very own critter genome published in GenBank,” Erill says.

Building independence

Many of the students who enroll in Phage Hunters don’t have previous research experience. So how do they go from rookies to competent, passionate, independent researchers who spend hours in the lab at a time? It’s all about the support system.

During the lab’s open hours (9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. every weekday), graduate and undergraduate teaching assistants take shifts to provide guidance. “The TAs really motivated students and provided a safety net for students with questions,” says Marty Lee ’17, biological sciences. Lee later became a TA for the course himself.

Caruso agrees that the undergraduate TAs are one of the secret ingredients for the program’s success. “The students are much more likely to ask their peer-level TAs questions and get help when they need it. Having them there allows me to interact with more students,” he says.

Beyond learning how to employ common lab techniques used in genetics work, the Phage Hunters students are learning how to ask the right questions, take risks, and troubleshoot: They’re becoming scientists.

“I am convinced that the best thing about the SEA-PHAGES program is the ownership aspect of it,” Caruso says. “The students have to be allowed to carry out their own experiments and fix their own problems. You’re there to help them when they fail, but they have to be allowed to fail.”

One day in the lab stands out for Kawa—a six-hour stretch where she was so captivated by the research, she just kept on working. “It was the happiest day thus far in my college career,” she remembers. “At that point I had thought I wanted to become a researcher and go into biotech, but that day my mind was totally made up, 100 percent. This is what I want to do.”

Collaboration on the cutting edge

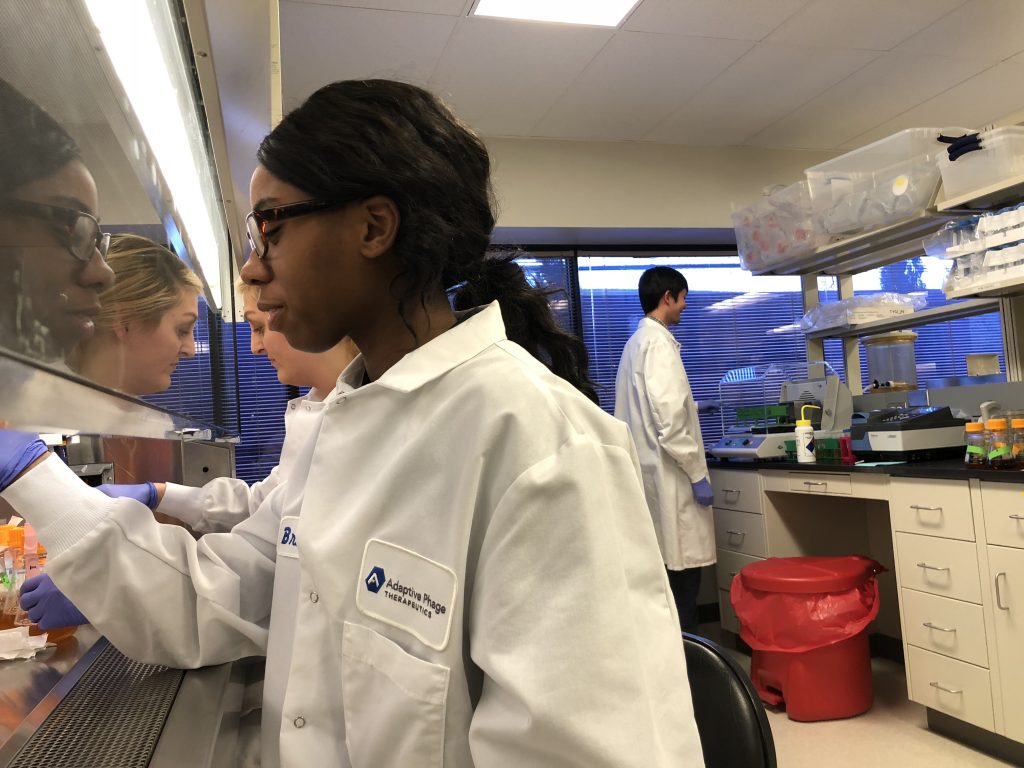

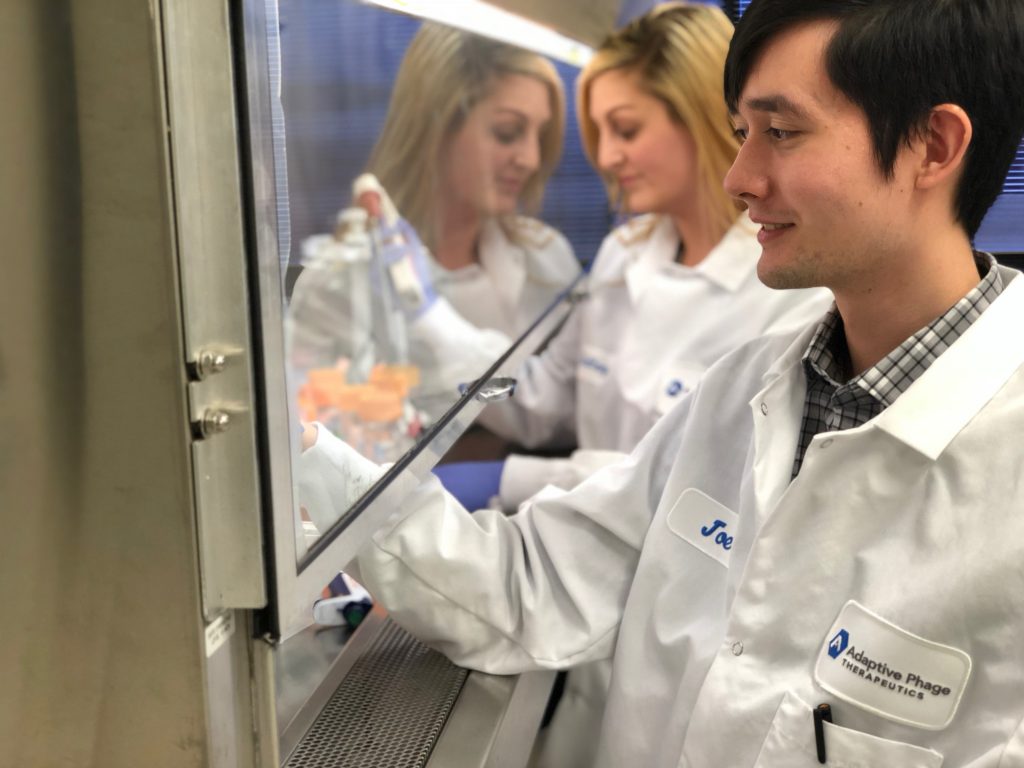

With five UMBC alumni at Adaptive Phage Therapeutics, which has a total staff of fewer than 20, “Our UMBC family mentality translated directly into our APT family,” shares Bri’Anna Horne ’17, biological sciences. “Because it’s so small, we work together, and we support each other for every single procedure we’re doing…It’s really great to have a team that you already have a working history with in a professional setting.”

The work itself is as rewarding as the atmosphere. “All the techniques we learned in Phage Hunters directly translate to the work we do in the lab on a daily basis,” says Kawa. And executing those techniques is saving lives. APT is working with the U.S. Navy to create a “phage bank” that can speed up the process of finding phages that can treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in patients who have run out of other options.

“It’s exciting for us, because we’re doing cutting-edge research, and we’re actually saving people’s lives,” says Horne.

Dang feels similarly. “Being on the cutting edge of biotech is really exciting… Just being right there, potentially changing history, is really exciting.”

For Joseph Tewell ’17, biological sciences, the work at APT is more personal. “I got more interested in phages because I’m part Filipino and there are a lot of issues with [access to] medicine in the Philippines,” he shares. “I thought phage therapy might be an interesting way to try to expand medical access in developing countries.”

Cool connections

The success of these alumni has resulted in a strong connection between the Phage Hunters program at UMBC and other local biotech companies as well. For example, Julie Norton ’15, biological sciences, M.S. ’16, applied molecular biology, works at Intralytix on Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

Erill first invited Intralytix staff to give a guest lecture for the Phage Hunters students in 2015. Today, Intralytix and APT both regularly guest lecture and advertise job openings to current students involved with Phage Hunters. Current UMBC alumni employees serve as unofficial recruiters, too.

When she meets with current students in the program, Horne highlights both the career opportunities she’s found in biotech, and the broader range of possibilities in the field. “I really love what I’m doing now,” she says. And that feeling is even more meaningful for Horne knowing that as a highly skilled professional in such a quickly growing technical field, there are now “so many options to explore.”

Banner image: UMBC students at work in the Phage Hunters genetics course. Photo by Steve Caruso.

All other photos are courtesy Bri’Anna Horne ’17.