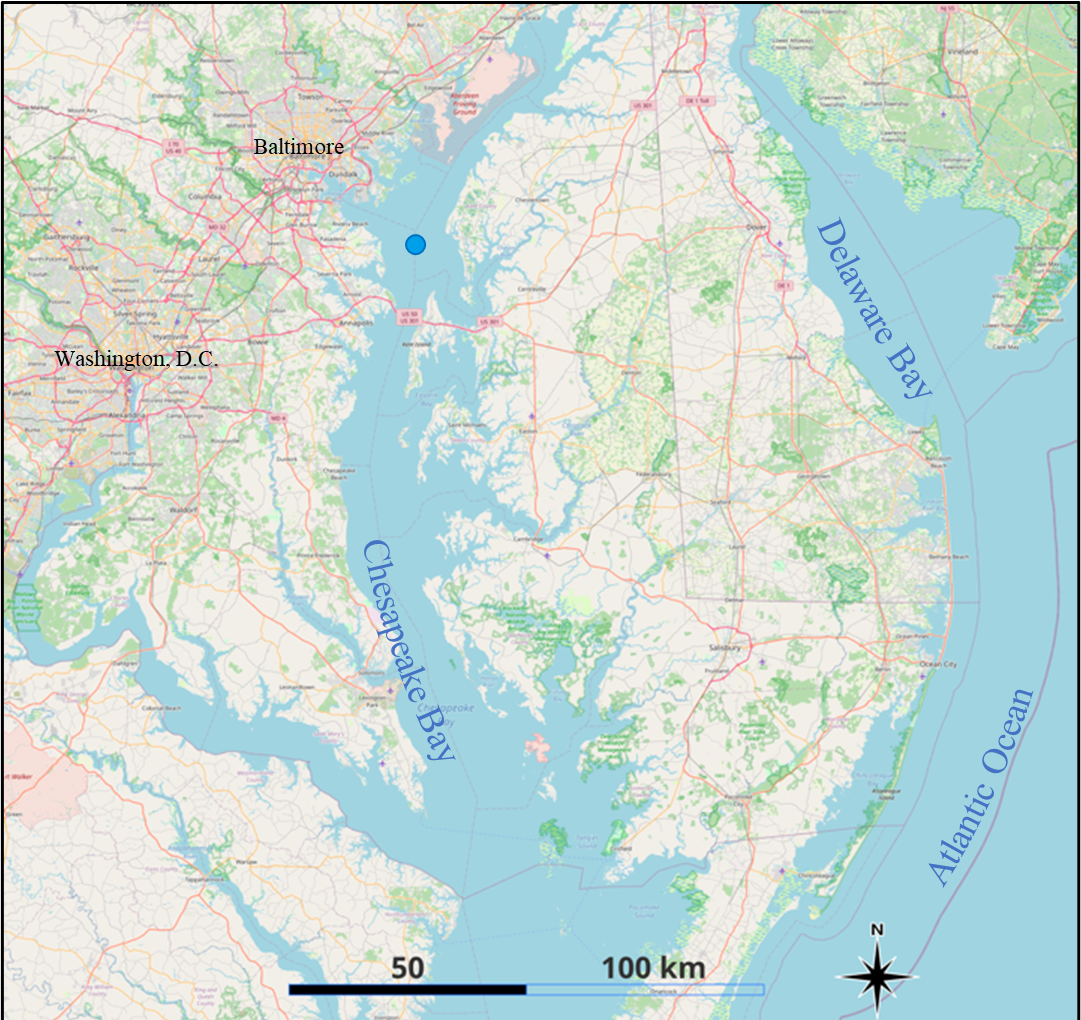

Climbing 30-meter ladders and avoiding osprey nests might not sound like typical activities for scientists who usually work with equations and models—but it’s all in a day’s work for Kevin Turpie’s team, which includes an international group of scientists and engineers from UMBC, NASA, the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS) and the Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ), also known as the Flanders Marine Institute, also in Belgium. Over the last 15 months, they have collaborated with Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) staff, with the blessing of the U.S. Coast Guard, to install, monitor, and repair a new instrument on top of a Coast Guard navigation tower in Chesapeake Bay near Tolchester, Maryland.

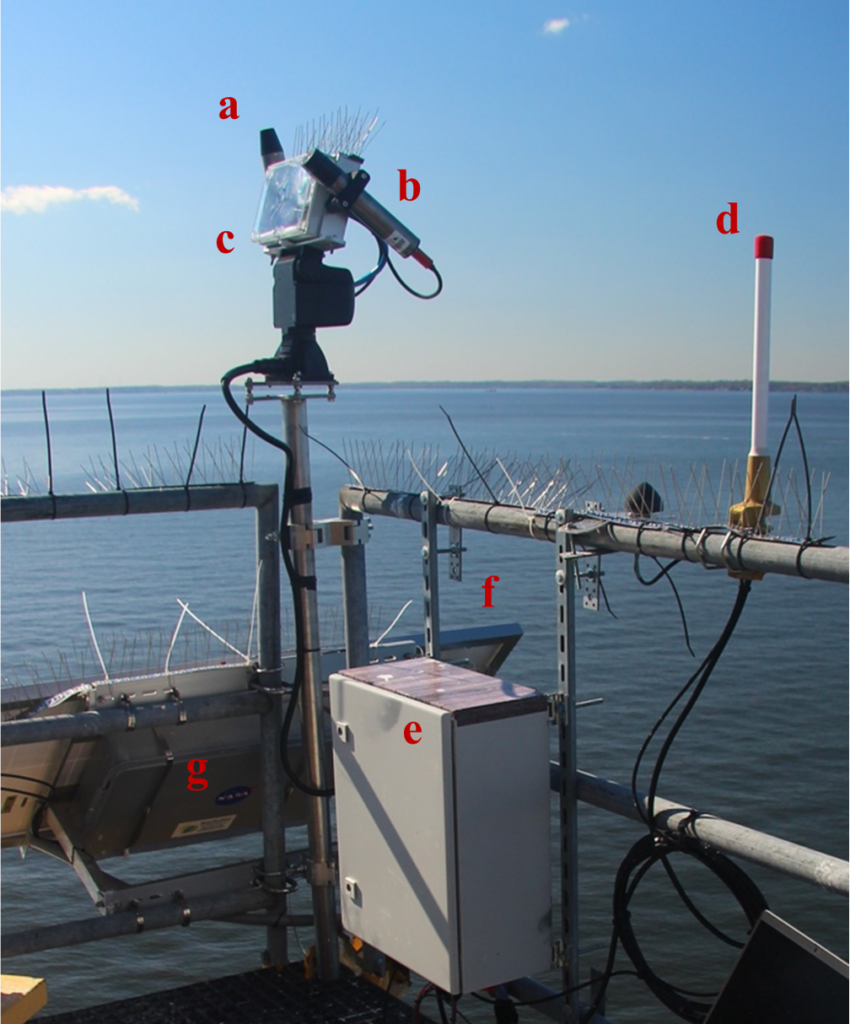

The instrument, called the Pan-and-Tilt Hyperspectral Radiometer (PANTHYR) and developed by VLIZ, is one of multiple PANTHYRs deployed worldwide. Each is part of the WATERHYPERNET—a growing network of automated instruments that provide measurements to validate observations from space. The WATERHYPERNET concept was developed by RBINS and VLIZ and supported by the European Space Agency (ESA). Another instrument called the HYPSTAR is installed at some other WATERHYPERNET sites, and the Chesapeake Bay station may add one in the future.

The Chesapeake Bay PANTHYR station is the first WATERHYPERNET station installed in North America; others operate off the coasts of France, Italy, Belgium, and Argentina. The new station “will provide a wealth of information regarding water quality and the environmental and ecological conditions in the Upper Chesapeake Bay,” says Turpie, a research associate professor with the Goddard Earth Science Technology and Research Center (GESTAR II), a UMBC partnership with NASA.

A “rigorous test”

The Chesapeake PANTHYR will also help validate data coming from the Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) aboard the recently-launched NASA PACE satellite, which also carries HARP2, an instrument designed and built by UMBC researchers. The station will also provide data to validate many other satellite missions, including NASA’s future Surface Biology and Geology (SBG) mission, part of the upcoming Integrated Earth System Observatory.

“Observations from space are critical to understanding how our planet functions as a system and how that system is changing. But such measurements are done in the harsh environment of space, looking through the entire atmosphere, and always from several hundred kilometers away,” Turpie explains. “So, we need to compare those data against the same kind of measurements taken at the surface. PANTHYR offers a rigorous test for PACE and its ability to glean vital information about our world’s most critical coastal resources.”

PANTHYR is the newest instrument in the WATERHYPERNET, a global network of instruments managed by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and supported by the European Space Agency.

A challenging work location

The Chesapeake Bay PANTHYR station was installed in July 2023, but encountered challenges due to winter weather, complex logistics, and the collapse of Baltimore’s Key Bridge and subsequent environmental threat assessments. However, after a repair mission in September 2024, PANTHYR is up and running again, and data are streaming in.

Arranging each trip to service PANTHYR is complicated. MDE staff pilot the boats that take the researchers to and from the site, and only tower climbers with special training can access the instrument. Calm weather is a necessity. Plus, in the spring, there’s always a risk that ospreys or eagles will choose the tower for nesting. That makes the instrument inaccessible if young birds are present.

But the team is committed, because the data PANTHYR produces are valuable. Every 20 minutes, PANTHYR measures the intensity of light encountering the surface of the water, the brightness of the sky, and how much light is reflected back from the water’s surface. PANTHYR detects visible and near-infrared light. These are some of the same data collected by satellites like PACE. WATERHYPERNET instruments also help scientists develop improved algorithms for processing the data and monitor phenomena like harmful algal blooms.

“Autonomous stations like this collect a wealth of validation information—more than we get from science cruises or other means, which can be very expensive,” Turpie says. “It’s exciting to get multiple observations a day of the changing water quality and ecosystem conditions of this important coastal estuary. For surface radiometry, this is very important in order to build up as many match ups with satellite observations as possible.”

Moving forward, UMBC is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the PANTHYR station. Turpie and his colleagues will be working hard to keep the station in tip-top shape so that it can continue to produce useful data and inform future satellite missions—with or without the “help” of neighborhood ospreys.