Katherine Carver, physics and mathematics, started off her UMBC experience with a big bang—participating in the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory CIRCUIT internship as a first-year student in spring 2023. Carver, now a rising junior, says she took advantage of every opportunity she could, from on-site guest lectures and panel discussions to informally networking with APL employees down the hall.

One of the panelists particularly caught her attention, so Carver approached her afterward—and in the two-hour conversation that followed, Kathleen Hamilton-Campos, an APL researcher, encouraged Carver to apply to the Space Astronomy Summer Program at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) at Johns Hopkins University, which Hamilton-Campos had completed in 2019. Carver received notification that she’d been selected as an intern while attending a Society of Women Engineers conference this spring.

This summer at STScI, Carver, a Meyerhoff Scholar, has been digging into developing open-source software that allows astronomers anywhere to analyze data arriving from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the most powerful space telescope ever launched.

Mission possible with James Webb

“The whole mission objective for JWST was to see further back into the universe than ever before or possible with the Hubble Telescope or any other type of telescope,” Carver explains. “With how light travels, if you’re looking at something four billion light years away,”—which JWST can—“that means you’re looking at it as it appeared four billion years ago. Which could be very useful for scientists trying to understand how our universe has come to evolve to its current state.” Indeed, Carver continues, JWST can observe light so old that it comes from nearly the beginning of the universe, more than 13 billion years ago—billions of years before Earth even existed.

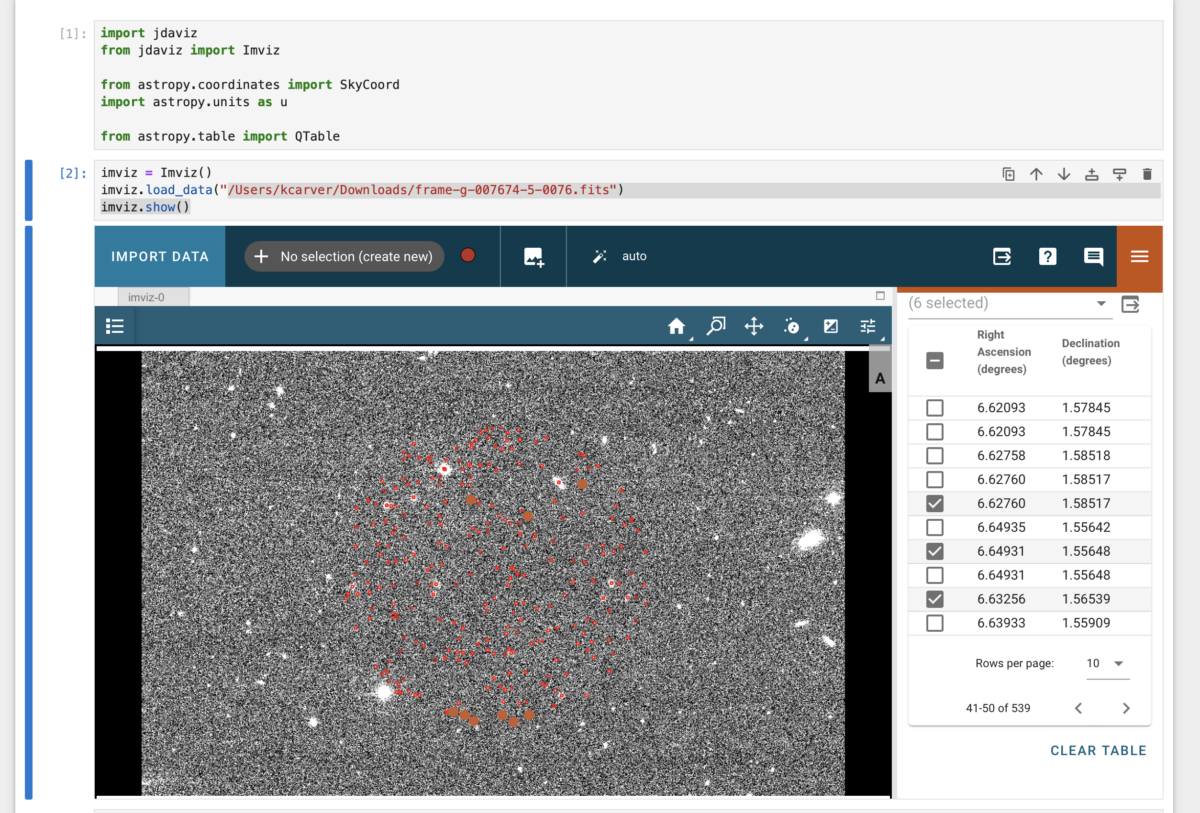

The analysis software Carver is working on is called Jdaviz, and it’s written in python. The data files are massive and complex, Carver explains, “so for a scientist who’s interested in only a brief part of the sky, or a particular source, like a star or a galaxy, it can be hard to navigate,” she says, “especially when some of these images have thousands and thousands of sources in them.”

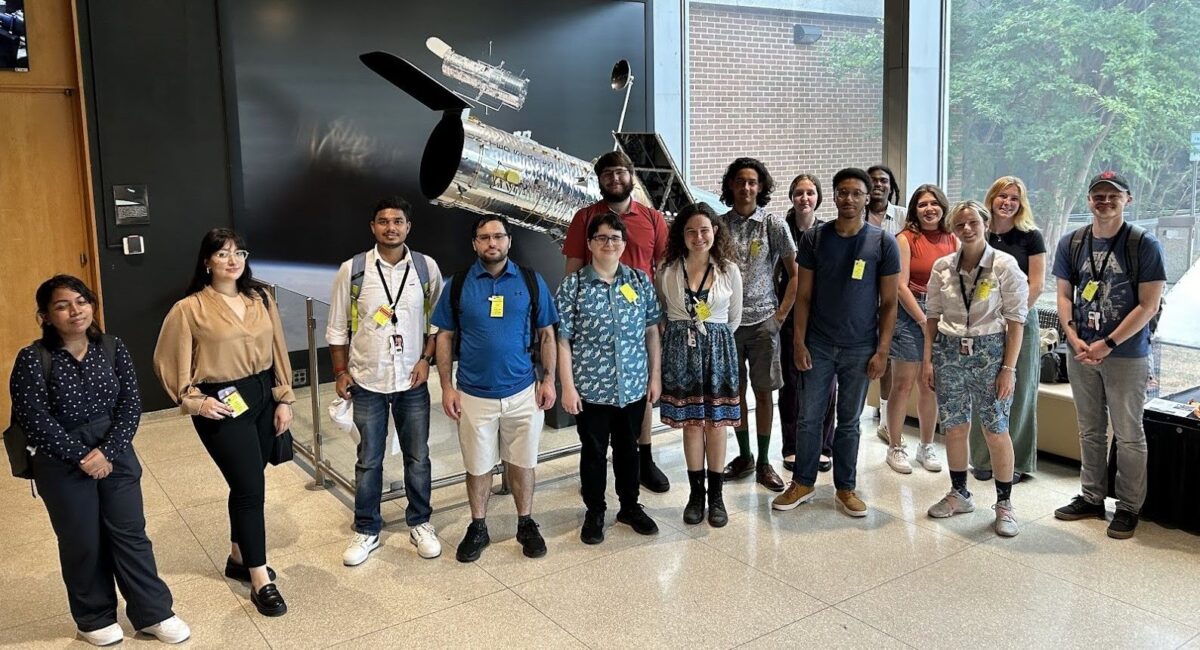

Carver’s contributions are making the data easier to work with, and as a result facilitating scientific discovery in a wide range of research areas. As part of the internship, she also went on a field trip to NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and saw where the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope—a telescope whose capabilities will complement JWST’s observations—is being developed.

“Be persistent”

Through her CIRCUIT and STScI internships, Carver, a rising junior, has already picked up valuable coding skills, including managing interactions between behind-the-scenes code and the user interface, debugging code with errors, navigating code sets that include hundreds of files that all need to talk to each other, and much more.

The computer science training is likely to come in handy in her future, she says, but she doesn’t expect coding to become her bread and butter. She wants to stay on the science side, using tools like Jdaviz rather than developing them—although her time coding will make her even more grateful for the programmers who do. This fall, Carver is excited to move in that direction by conducting research with UMBC astrophysicist Adi Foord.

Carver has some words of encouragement for students just getting started on their research journey.

“There’s no hurt in putting your name out there, even if you feel like you will get rejected. Sometimes you might see the final polished picture, like, ‘Oh, she’s done research at APL. She’s done research at STScI. Those are really competitive’—but I also got a lot of rejections,” Carver says. “Shoot for the internships even if you feel like you won’t get them. Be persistent, ask around, talk to your professors. And then once you are there, take maximum advantage of every opportunity.”

Tags: Career Center, CNMS, Physics, Undergraduate Research