A new course in UMBC’s Department of Mathematics and Statistics is having a positive impact on student success in a notoriously difficult course for math majors everywhere. Two new papers by UMBC mathematicians and members of UMBC’s Faculty Development Center strongly suggest that MATH 300: Introduction to Mathematical Reasoning (IMR) is helping students succeed in MATH 301: Real Analysis, the first course math majors take that relies on one’s ability to construct and analyze proofs, rather than just do calculations.

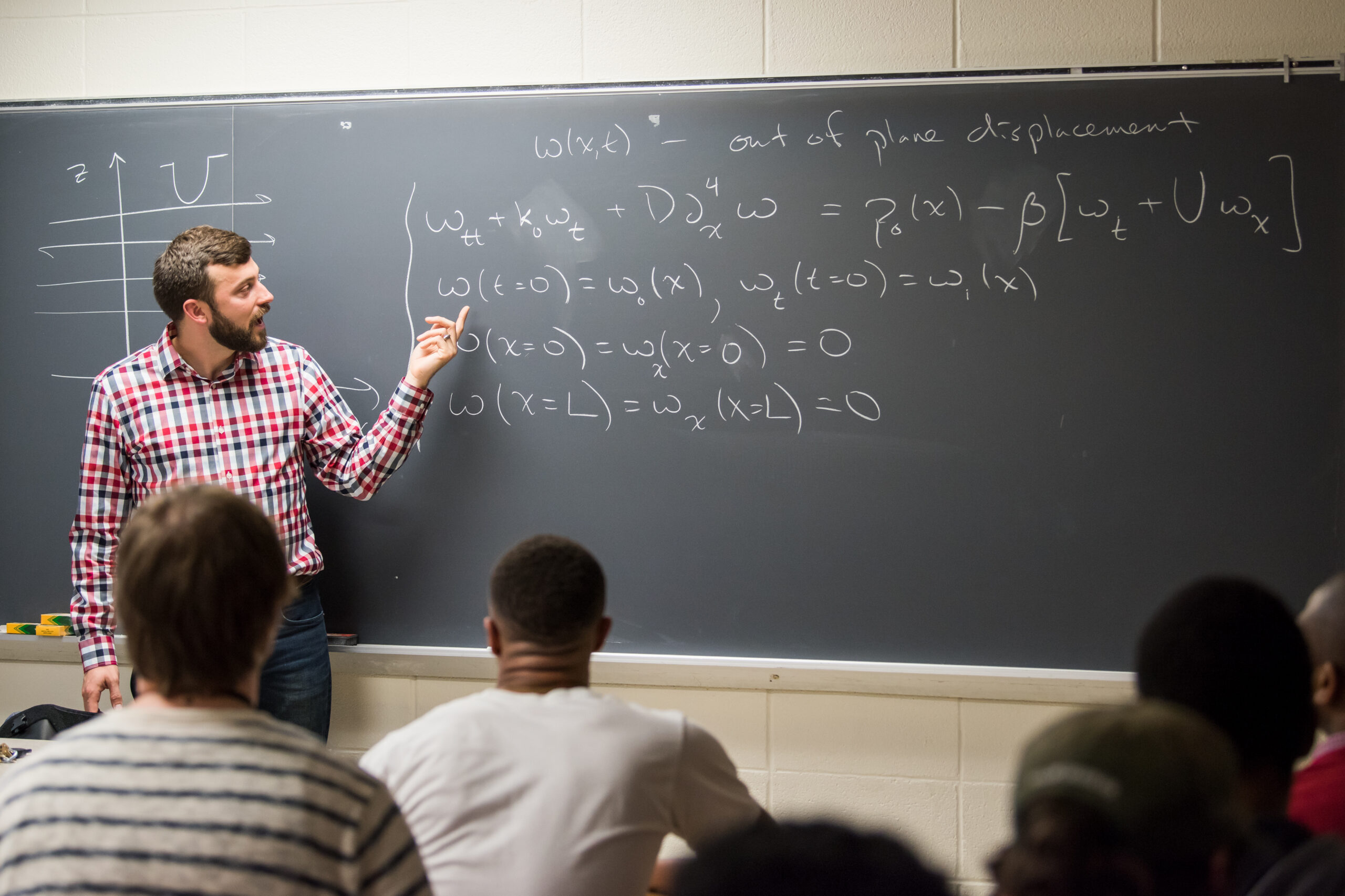

In Real Analysis, “We’re switching gears of how students think. They go from calculational things to proof-based work,” says Kathleen Hoffman, professor of mathematics and lead author on the new papers. “Now your solution is a paragraph that you have to write in full sentences. It has to have logical structure. It has to start with a hypothesis and end with a conclusion. It’s a big hump for students to get over.”

Real Analysis is easily one of the most challenging courses for math majors nationwide, Hoffman says. Over the years, many institutions have introduced a preparatory course that teaches students how to develop proofs without requiring them to learn new math content at the same time. The conventional wisdom is that these courses help, but almost no one had conducted a rigorous study to find out.

“There was a huge gap in the literature,” Hoffman says.

Forming the team

UMBC math faculty had seen the need and been talking about adding a dedicated proof-writing course for years, but it hadn’t quite come together. Hoffman jump-started the process by applying for a Hrabowski Innovation Fund Grant in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning category. These awards support faculty who want to do ambitious projects that they might not otherwise have bandwidth for.

When the award was funded, Hoffman formed a team with Justin Webster, associate professor of mathematics, and Kal Nanes, associate teaching professor of mathematics, to design the course for UMBC. Webster had re-designed and updated one of these proof-writing courses at his previous institution, the College of Charleston. The math team also worked with staff in UMBC’s Faculty Development Center to design a rigorous study to evaluate the course’s effectiveness over time. The team knows of only one other such study, from the 1980s, despite the rising incidence of proof-writing courses at universities nationwide.

Hoffman, Webster, and others believed that IMR would help UMBC math students, and informal observations supported their hunch once the course launched. These publications provide statistical analyses to back their intuition, and now Retrievers and students from other institutions can benefit from their successful formula.

Thinking about thinking

The first paper, published in a special issue of Educational Sciences, focused on written reflections the students completed every week along with their proofs. Prior research suggests that students tend to struggle in specific skills related to proof-writing, so the students were required to address how well they thought they did on each of four skills in their reflections.

“Students who did very thoughtful responses did much better in this course, but they also did much better in Real Analysis, where they didn’t do any reflections,” Hoffman says. The reflections “give the students a framework for understanding what they know and what they don’t know. It gives them the words to use.”

The study analyzed the quality of the reflections, but not necessarily the content. It didn’t seem to matter exactly what aspects of proof-writing the students addressed in their writing—simply the act of metacognition, or “thinking about thinking,” seemed beneficial.

The correlation was strong, but Hoffman admits the study does not prove causation. Strengthening the evidence, though, is that thoughtful reflections in IMR were not correlated with success in its prerequisite course, MATH 221: Introduction to Linear Algebra. That suggests the reflections, and potentially other elements of IMR, were the difference-maker for students moving forward.

A solid foundation

A second paper, published in the International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, compared students’ grades in Real Analysis depending on whether or not they had taken the proof-writing course. The findings showed that IMR did not much affect the outcomes for students who earned As in the prerequisite linear algebra course—they were also likely to do well in Real Analysis whether they took IMR or not. However, students who earned a B or C in the prerequisite course were much more likely to successfully complete Real Analysis if they had taken IMR.

The researchers also received overwhelmingly positive feedback from students who had taken IMR about its benefits. One student said,

“I feel like [IMR] gave me a solid foundation in understanding how to write proofs, which allowed me to come into [Real Analysis] with a bit more confidence. Without it, I probably would have struggled through [Real Analysis] since I would have been learning how to write proofs and the [Real Analysis] material at the same time.”

Based on the results of these studies, the UMBC mathematics and statistics department has decided to make IMR a required part of the curriculum for math majors and minors. Minors used to take Real Analysis as their terminal course, but now they take IMR. For majors, IMR provides the foundation needed to support success in Real Analysis.

More than pushing symbols around

When he took it as an undergraduate, an IMR-type course “was the thing that made me want to be a math major,” Webster says, so designing this course for UMBC was an exciting prospect. Becoming proficient in writing and analyzing proofs, rather than doing calculations, is like “writing versus writing literature,” he says—you have to spend a lot of time thinking about what you’re trying to accomplish and how to structure your arguments. You can’t just “plug-and-chug,” applying various theorems and techniques to instances of a given type of problem. “Math isn’t just the act of pushing symbols around,” Webster says.

To prepare students to write mathematical literature, Hoffman says that in IMR, “In one sense I’m teaching math, but in another sense I’m not. I’m teaching them how to think—how to structure their argument and express it clearly.” Almost never can a student simply sit down and write a proof in one sitting, like completing a problem set in prior math courses. It’s more like writing a paper.

When you work on a proof, “You think, you don’t get it, you go do something else, you think, ‘Oh, I think I know what to do,’ you come back, and that is normal,” Hoffman says. “They have to understand, this is not instant gratification—you will struggle with this and I’m expecting you to. It’s inevitable that they will struggle—I’m teaching them to persist through the struggle.”

A collective commitment

The studies would not have been possible without support from the Faculty Development Center. While many faculty might like to conduct more rigorous analysis of their teaching methods, it’s not their area of expertise. “If you want people like me who do disciplinary research to engage in pedagogical research, you have to give me some help,” as Hoffman put it.

That’s where the FDC came in. Several staff members became involved in the project, including Tory Williams, Jennifer Harrison, Kerrie Kephart, and Linda Hodges, adding their individual areas of expertise.

“The math faculty have deep expertise in math pedagogy, but needed our support to help plan the intervention, design the research study, and analyze the data. The project required all hands on deck.” shares Kephart, co-author on the written reflections study and interim FDC director. “As a qualitative researcher with expertise in the teaching of academic writing, I enjoyed the challenge of figuring out how to study the effects of incorporating reflective writing into a math class.”

The project is also a demonstration of the math department’s commitment to supporting student success, even if that required some culture change. Since IMR’s initial offering in 2019, several additional math faculty have taken on teaching the course. Each time someone new takes it on, they work closely with experienced instructors, and all sections of the course are closely coordinated to ensure quality and consistency for students.

The project is a masterclass in recognizing a challenge (a high failure rate in Real Analysis) and taking creative, concerted, and collective action to address it, with very positive results. “After realizing there was a gap in students’ preparation, a group worked together to fill it, and in the process learned a lot about how to measure progress in math education and pedagogy,” Webster says. “We leaped at this opportunity to effect change and measure outcomes in a novel and modern way.”

And because they carefully evaluated the project’s effects and published the results, now other math departments can benefit from their findings. That possibility was a highlight for Kephart. “Since our work in the FDC generally supports faculty, teaching, and learning here at UMBC,” she says, “it’s exciting to make a contribution toward the development of math pedagogy beyond our campus.”