|

There is no tradition of singing in harmony in Ibiza and Formentera, and most songs, except in the city, are sung alone or in duos or very small groups. Cançó redoblada, Cançó glosada. These are the two genres of Pityusan traditional singing considered emblematic of the islands. The most striking and mystifying aspect of the vocal repertoire is the technique known as redoblar, in which each couplet ends with a sort of single-pitched guttural yodel, the redoblat, which does not seem to exist anywhere else. Alan Lomax described the redoblat as “....a hard reedy voice...ululation which resembles sobbing or sometimes stuttering, made deep in the back of the throat below the glottals...” and also as a “ululation delivered with nearly closed mouth, from the palate with a slight shaking of lower jaw.” He quotes one Ibizan singer as having specified that it was a strong sound made “deep in the throat”, and “shaking your jaws.”(unpublished field diaries). Men and women’s redoblat sound quite different, the men tending to articulate the syllables with initial “y” (yeyeye) and the women with the neutral vowel only (Escandell 38). The women sometimes insert a “yol”, a quick ascending glissando into the redoblat. Escandell describes the redoblat as a rapid trill between the lowest note of a melody and a fifth or sometimes a sixth above it, emphasizing the lower note (36-37). Various possible origins of the redoblat have been proposed over the years, usually tending toward a vague attribution to “Moorish” or “North African” roots, but no satisfactory solution has been found. Jaume Ayats (2001) has sensibly cautioned, though in another context, against the facile attribution of mysterious origins to “Moorish” roots: the tendency to identify the redoblat as vaguely “North African” should perhaps be seen in this context. A couplet is known as a mot, and groups of mots form a cobla, maintaining the same rhyme or assonance throughout. The first mot of the song is the cobleig or cobletjoll, a sort of refrain which then ends every cobla. The number of coblas per song in a formal event is now pre-set so that each singer has a chance to perform; however, traditionally, the pattern is not necessarily consistent. The redoblat may be long or short, traditionally alternating long and short redoblats, although this is not always done in practice. It begins with the last syllable of the preceding word, and ends with the first three syllables of the first word or words of the next mot, without pause. There is then a very brief pause, very often cutting the next word off after the first syllable, and typically omitting a syllable or even a word, so that the listener must have the linguistic and cultural background to mentally supply the missing text. The singer continues with the rest of that mot (6), and this pattern is repeated until the end, when the opening cobleig returns and the song ends with it, abruptly, almost spoken rather than sung, and without redoblat. The few younger people who perform this genre today may alter this structure so that it is simpler, with the redoblat ending each mot, and without omitting syllables. The redoblat technique is applied to more than one genre. As a song duel, a porfèdia (or cançó besones or regateix), it often takes place between a man and a woman. The structure described above is maintained by each singer during the lines he or she sings. At the end of his or her turn, the singer stops with no redoblat and the other singer starts immediately, with no pause at all, or even begins before the other has finished his or her redoblat. The end of the song is abrupt, with no redoblat. The song ends abruptly, with no redoblat. The Caramelles also use the redoblat (see below). The singer beats, in many but not all cases with precision, a small two-headed drum (tambor) held on his or her lap, and with the free hand, the arm resting on the drum, shades his or her eyes, often with a handkerchief (mocador), while singing and playing.

glosa singers and composers are respected as much as men, in a

cantada a married or engaged woman must request her partner’s permission in order to sing.

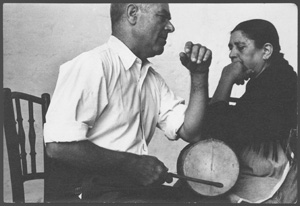

Vicente Ribas ("Curt", "Curtet" and Catalina Ribas ("na

Perancona"), vocals and tambor

Ibiza, July

1952

This porfèdia, a witty exchange of insults, is sung by a

well-known brother and sister duo. The tilde ~ indicates a break

in a word and the square brackets syllables or words which the

singer omits after the pause but which are understood by

listeners familiar with the genre.

Porfèdia (Song duel)

Transcribed by Esperança

Bonet and Jaume Escandell, translated by Judith Cohen.

Man:

Bon amor jo et venc a veure diumenge i dia fe’ner,^^^^

i et dec~ [dur en] sa meua idea, sa teua jo no la sé.^^^^

Woman:

[És] molt mala de conèixer, jo cantant te la diré,^^^^

pots ven~[ir] quan te parega ses voltes que et caiga bé,^^

mai t’he~ [pri]vat sa conversa perquè ets bastant musiquer.^^^^

Man:

Sense faltar-te es respecte ni fer-te es parlar grosser,^^^^

i t’he~ [‘ri]bat a dar a comprendre lo que a jo em vendria bé.^^^^

Woman:

Som bastant desintesa per cosa que no em convé,^^^^

i tu sem~[pre] vas ala estesa, pareixes es gall faver.^^^^......

Man:

Sweet love, I’ll come to see you, Sunday and during the week.

I have to tell you my thoughts; I don’t know what yours are.

Woman:

They’re hard to understand; I’ll tell you by singing,

you can come whenever you like, whenever it’s a good time for you.

I’ve never told you not to speak [with me], for you’re a good musician.

Man:

Without failing in respect for you, or speaking inappropriately,

I must have you understand that it would be a pleasure for me.

Woman:

I don’t pay much attention to things which aren’t good for me,

you always go about with your wings spread like a rooster strutting

about... There is a

popular conception of the porfèdia (song duel) and the glosa

as being improvised genres, as is the case with similar genres in

several other parts of Spain and the Baleares. However, in the Pityusans,

song lyrics are often at least partially prepared ahead of time, either

long before the occasion or even during the hour before the singer is

going to be called upon. Experienced singers have a wide repertoire of

stanzas and formulas, from which to select or adapt, for each singing

occasion, and song duel couples often not only know each other very

well, but are siblings or a married couple, who may prepare the song

duel together. Improvisation may take place to varying degrees within

the song, and sometimes more and more as the song session goes on.

Josep Marí Prats (“Pep den Rotes”), vocals and

espasí; Josep Cardona (“Pep Pujoletí”), vocals and castanets;

Miquel Bonet (Can Pep den Frare), flute and tabor.

Sant Josep, Ibiza, July 18, 1952.

At least since the19th century, there have been

specialists in composing these song genres recognized throughout

the island, and whose songs were learned and performed by

others. Blasco Ibañez describes one young singer-composer at

length in his novel, and Samper refers to one in particular who “did

us the honour of singing a song he had not allowed anyone to

copy” (Massot: IX 46).

The redoblat technique is also part of Christmas season,

and, formerly, Easter Sunday musical occasions, in the

caramelles and sometimes in the gotxos song

genres These genres have fixed words. The caramelles,

whose name derives from the old caramella, a simple

single-reed wind instrument, are sung by men only; these must be

older men with good community standing. They are accompanied by

the same instruments used for dancing: three-holed pipe and

tabor, large castanets, and scraped sword (espasí). The

two men sing couplets in turn, and perform the refrain together.

The flute accompanies this singing with a melody which appears

to have little connection to what the men sing, though both

their melody and the flute melody are specific to the

caramelles genre. The words are a version of the “Joys of

Mary”, using very archaic language.

Cobla I.

Both: [Sant goig] prencipal, és nat fill de Déu;^^

Mare esperital, - Qui em vol oïr?^^

Sant goig~ [pren]cipal és nat fill de Déu.^^^^

First voice.

Fonc lo primer goig, Verge, quan vós é ^^^reu,

Verge~ , vós érau s´unic fill de Déu^^^^,

l´àngel~ [mo’n tra-]mét; diu San Gabriel^^^

missa~[-tge]c cortés qui mo’n serà dat:^^^^^

Second voice:

Bendit i promès diu que ara vendrá^^^

i s´en~[car-]narà, Verge, el fill de Déu,^^

i el fill~[de] Déu diu: - Qui em vol oïr?^^^........(8)

Ses Caramelles/The Seven Joys of Mary

(Verse I)

(mp3 file)

Josep Marí Prats (“Pep den Rotes”), vocals and espasí; Josep

Cardona (“Pep Pujoletí”), vocals and castanets; Miquel Bonet

(Can Pep den Frare), flute and tabor.

Sant Josep, Ibiza, July 18, 1952. |